Dear Dr. Zoomie – I run a radiation safety program at a small laboratory and I’m working on our emergency response procedures. I was wondering if you can tell me what goes into responding to a radioactive spill.

Good question – and a very good topic! I ran an academic radiation safety program for several years and spills were most common type of incident we had; on average, about one spill a week. Most of these were fairly minor – a researcher with a leaky pipette for example, or a little spray from around the cap of a stock vial when you open it up. Of course you can have larger spills too – we had a researcher once drop 100 ml of radioactive solution on the floor, and (in our hospital) had an incontinent patient who urinated on the floor – nearly a liter of radioactive urine. Anyhow, what it means is that you are likely to have spills ranging from nearly invisible to fairly significant, and you have to know how to respond.

The acronym we learned in the Navy was SWIMS – it stands for:

• Stop the spill

• Warn other people

• Isolate the spill area

• Minimize radiation exposure

• Stop ventilation if possible and if it will help

Here’s what that means….

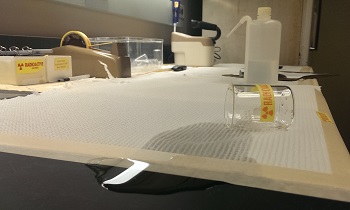

Stop the spill doesn’t mean cleaning it up so much as stopping it from getting worse. So you want to pick up (wearing gloves so your hands don’t get contaminated) the bottle or vial or whatever you might have dropped or knocked over (if that’s what happened) and put some absorbent materials over whatever spilled to keep it from spreading further.

Warn other people about the spill. Let the RSO know about it so he or she can send help. Let people in the vicinity know about the spill so that they don’t walk into your spill area (also so that people who might be contaminated – anybody closer than about a meter away – stay put so they don’t spread contamination around). Even if it’s a minor spill you have nothing to lose by warning others – especially Radiation Safety.

Isolate the spill area to keep people from wandering in and getting contaminated. This means putting up physical barriers – rope, tape, even a table across a doorway – something that people have to physically move in order to cross. What you should do is to give yourself enough room to work – at least a meter past the furthest droplet you can see. Once a spill boundary is put up, you shouldn’t let anybody enter the spill area unless they have proper protective equipment (PPE) – at the least, gloves, shoe covers, and a lab coat. And once somebody is inside the spill area, only Radiation Safety should be permitted to survey them out of the area.

Minimizing radiation exposure is not so much a procedural step as a way to approach the incident. Remember – there is nothing life-endangering about a spill and you don’t have to rush in, unthinking, to save the day. Take a moment – give yourself the luxury of thinking about what’s happened and the best way to deal with it. Do you need respiratory protection? Do you have your gloves on? Do you have the right materials on-hand to clean it up? Or do you need to wait until you can get the right materials to clean it up safely? By doing this you’ll be minimizing everybody’s exposure.

Stop ventilation if possible and if desirable – but this isn’t something that needs to be done every time. First – running the ventilation can spread radioactivity through the ventilation system, which can cause problems. In addition, air blowing on a spill – especially if it’s volatile – can cause the activity to go into the air, turning it into an inhalation concern. So if you can turn off the ventilation then it will keep these things from happening. On the other hand, if you don’t know how to turn off the ventilation or if you have to stand in the middle of the spill to do so then you might want to leave it be for the moment. Oh – also, don’t forget to stop ALL the sources of ventilation if you make this decision. This includes, say, refrigerators and freezers (the compressor blows out air), pumps (the motors usually have vents), and even computers or projectors that have vents that might blow onto your spill.

Another quick comment about these actions – SWIMS is a mnemonic to help you remember these steps – they do not have to be done in that order. Just make sure you remember to do them!

Once you’ve got through these actions you’ve earned the right to take a short break – at this point things aren’t getting better, but they’re also not getting any worse. So take a minute to think about what you’ve got and the best way to clean it up and restore the area. Cleaning up is part of this – here’s a little on that.

• First, work from the outside of the spill area towards the inside, and to work from the top to the bottom (if the spill is, say, on a table or countertop and has dripped onto the floor).

• Most of the time, commercial cleaners will work just fine; although you might want to use a specialty cleanup product if you have radioactive metals (cobalt, cesium, etc.) in the spill – this is mostly at nuclear power plants, though, and not so much at universities.

• As you clean, you should put the cleaning materials (paper towels, bench pads, or whatever you’re using) into a plastic bag as you use them. If someone is holding the bag they should be wearing gloves to keep from being contaminated. And every now and again, survey the cleaning materials to make sure your cleanup is having an effect – if you start finding that no contamination is coming off on the paper towels (or whatever you’re using) then either the area is fully decontaminated OR the contamination is fixed to the surface and you should move on to another location.

• Finally, you’ll have to survey the entire spill area when you think cleanup is completed in order to show that contamination levels are acceptable. Usually this means less than 1000 dpm per 100 square cm, but these vary depending on the radionuclide and the type of radiation it emits. A good reference is a document called RegGuide 18.6 – it’s a Nuclear Regulatory Commission regulatory guidance document that, even after nearly 40 years, is still the standard reference on the issue.

There’s a lot more on this topic than what I’ve got here, but what I’ve got here will get you off to a good start. Hopefully you won’t have to use this often but, if you do, I hope this helps out.