Roentgen’s discovery of x-rays was easily the most exciting scientific discovery of its time. Here were invisible rays that were fairly easy to generate and that could pass through solid matter – not only that, but they could even show you what was inside that matter they’d passed through! In the case of the human body (one of the first and most-frequently objects to be x-rayed), these rays would show bones – both broken and whole – as well as internal organs and any foreign objects that might have ended up within the body.

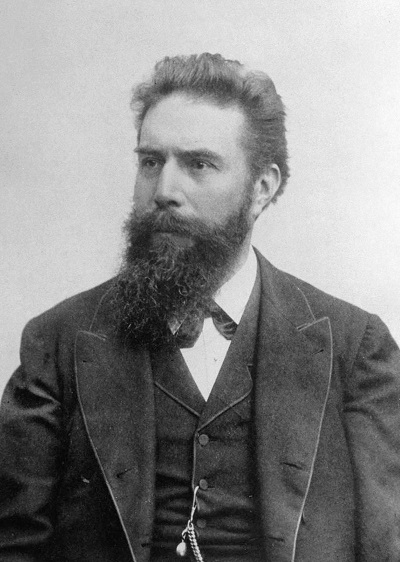

Reference: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilhelm_R%C3%B6ntgen#/media/File:Roentgen2.jpg

Now take a moment to consider what this would mean to a doctor. Say, for example, a mother brings in a child she thinks has swallowed a key. The child appears to be in pain, which would seem to confirm the key-swallowing, so what do you do?

You could simply watch and wait to see if the key passes through – but what if it’s hung up in a bend of the intestine and tears its way through into the abdominal cavity?

You could perform exploratory surgery – but where do you cut? And what if you search and search and don’t find the key? Was the mother wrong and the key was simply lost (in which case the surgery wasn’t necessary), or did you miss it somehow?

And now you hear of this device that takes out all the guesswork – you don’t have to wait and hope, you don’t have to cut into an otherwise healthy child, wondering if you’re doing the right thing. One quick picture and you know exactly what’s going on, and likely what you need to do. This has to have seemed nearly miraculous to doctors at that time.

With all of the x-rays that were being taken, physicians noticed they were starting to see a new kind of burn on their patients, sort of like a sunburn, but a little more painful. With time, they noticed a correlation between these burns and patients who’d had x-rays and it was easy to assume that the x-rays were causing the burns. But that was an assumption, not proof.

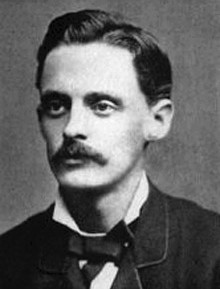

Elihu Thomson (March 29, 1853 – March 13, 1937) was an English-born American engineer and inventor who was instrumental in the founding of major electrical companies in the United States, the United Kingdom and France.

Enter Elihu Thomson, a physicist living in Boston. Hearing speculation after speculation on both sides of the matter, he decided to take matters into his own hands (so to speak). Over a period of time in 1896 (the year after Roentgen’s discovery), Thomson stuck his little finger, partly protected from the radiation with a small amount of lead, into the x-ray beam. It didn’t take long for him to build up enough of a burn on the unshielded part of the finger to convince himself that the x-rays were causing the skin burns.

These earliest days of x-ray use saw the development of what are now fairly standard radiation safety practices – the use of lead for shielding, the use of photographic film (actually, glass plates at the start) for personal dosimetry, limiting exposure by reducing the amount of time spent in a radiation field, and more. In fact, many of the radiation safety practices that I use today originated during these years.

The reason that safety practices were developed so quickly is that radiation injuries began piling up. To quote EF Lang in a column titled From Earlier Pages…. in the October 1978 edition of the American Journal of Roentgenology, “Percy Brown, in his book American Martyrs to Science through the Roentgen Rays, records a litany of sorrow, and describes numberless unsuccessful skin grafts and gradual dismemberment.” (https://www.ajronline.org/doi/pdfplus/10.2214/ajr.131.4.734) Once radiation had been proven to be dangerous, there was every incentive to learn how to work with it safely.

At this same time, medical professionals were taking their explorations of radiation even further. It’s not a great stretch, for example, to wonder if radiation can burn a tumor as easily as a finger, and then to begin experimenting with radiation therapy. This led to the beginnings of radiation therapy – inserting small capsules containing radioactivity into tumors as well as exposing them to radiation from x-ray machines and from sources outside the body.

While oncologists were learning to use radiation for cancer treatment, others were seeing what else it could treat. It’s hard to find diseases that are more important to treat than cancer, as a result, many of these experiments seem frivolous or even silly today. Radiation was known to cause hair loss, for example, and one early experiment involved using radiation to remove women’s unwanted facial hair. Less frivolously, there were also experiments trying to treat lupus and various diseases of the nervous system using radiation – the latter hampered by the fact that nerve tissue is the least sensitive in the body to radiation damage.

For a few decades, radium was fairly widely used in medicine, applied as a source inserted into diseased tissues, administered as a paste or ointment, even drunk as a medicine. As a personal aside, as a pre-teen living in an apartment above his uncle’s medical practice in the 1940s, my father often signed for packages of radium that my great-uncle used to treat his patients.

Sadly, many of these treatments were worthless or even dangerous. A radium-based “medicine,” Radithor (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radithor), contained distilled water into which at least 1 µCi of radium had been added; it was advertised as helping with any number of health issues and, such was the luster of radium at this point in history, these claims were assumed to be correct. Thus, when an aging Eben Byers, a former amateur golf champion and perennial ladies man, injured his arm in 1927 and a physician recommended Radithor to him, Byers accepted the advice without question. He continued taking it regularly until 1930 when his teeth started falling out and his jaw fell off. In 1931, the company that made Radithor was ordered to stop making the compound; Byers died the following year.

As the relative ignorance of radiation health effects of the earlier years began to be replaced by increased scientific and medical understanding and as the public began to hear stories of the effects of these patent medicines as well as the cases of the radium watch dial painters the market for patent medicines shrank and the public’s initial fascination with radium and radiation turned into a more appropriate caution. At the same time, the medical community had accumulated a degree of caution, based on accumulated experience, and had backed away from its initial enthusiasm for radiation, using it primarily for cancer therapy – the field of diagnostic nuclear medicine was still a decade in the future.

Jumping forward to the 1990s, I spent some time working for the Ohio Department of Health as a radiation safety professional. One of my tasks at one point was to try to locate some of the sites in which radioactivity might have been used in the past – virtually all fell into one of two categories, former manufacturers of self-luminous paints and products and former medical facilities. We found a good number of both; most didn’t appear to be contaminated and, of the ones that were, the majority were not too bad. In addition, the state-funded a few “radium round-ups” in which anybody could turn in any radium source with no questions asked, the idea is to simply collect as much as possible for disposal. But there’s still radium out there – in 2002, as Radiation Safety Officer at a university in upstate NY I was asked to take custody of a small foil containing several mCi of radium – it had turned up in a railroad gondola car carrying scrap metal to a plant in Indiana. While working for New York City in 2010 we found a storage area that contained a large number of radium-dial compasses, several of which were leaking contamination, and even more recently, a friend of mine found a whole curie of radium in a garbage truck. Along with the rest of the radium that’s found in public places, it was shipped for disposal – in spite of its early promise, we just don’t use radium anymore.