Hi, Dr. Z – hoping you can help with something that’s bothering me lately. I read a story a while back about a radioactive waste site in New Mexico that’s received over 14,000 shipments. Not only that, but a lot of those shipments are plutonium! I’m not sure I want to drive in New Mexico anymore – with that many shipments it seems that every other truck on the road must be filled with radioactivity. How can this be safe?

Wow – that does sound like an awful lot of waste shipments, doesn’t it? And the “P” word (plutonium) can raise the level of concern even more. First, let me talk about the number of shipments, then I’ll get into the other stuff.

Fourteen thousand shipments sure sounds like a lot – but that’s 14,000 shipments since 1999, when the waste site (it’s called WIPP – the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant) first opened. That’s 25 years, which is 1300 weeks, which means that there are about 11 shipments to WIPP weekly. That comes out to about 2 shipments each day – there are many more WIPP staff driving on the roads in this part of New Mexico than there are radioactive waste trucks – and most of the trucks are carrying groceries, building supplies, gasoline, and all the other supplies that keep the towns and villages running. So, yeah, that’s a lot of trucks carrying waste over a quarter century, but it’s not very many trucks at any one time.

OK – with that out of the way, let’s go back and see what WIPP is, how it’s designed, and how it can safe, even with all that plutonium.

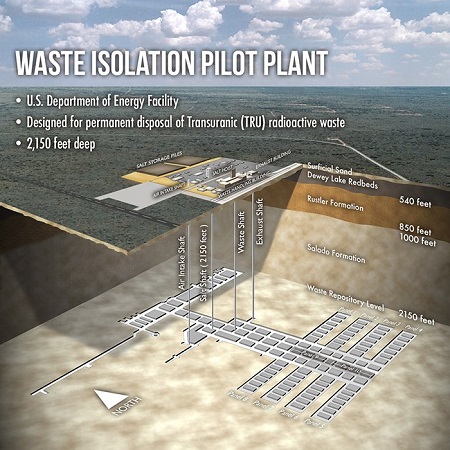

Every time a nuclear reactor operates it produces what are called transuranic elements (abbreviated TRU); these are produced when neutrons are captured by uranium to form neptunium and plutonium and these elements can capture more neutrons to form even heavier elements. These transuranic elements are different from other radionuclides – they tend to emit very damaging alpha radiation, the heavier ones can spontaneously fission (emitting equally damaging neutrons), and they can be both chemically and radiologically toxic. On top of that, some (e.g. Pu-239) are fissile. In the 1950s the National Academies of Science recommended that the unique combination of risks posed by TRU called for a different disposal scheme than for other radioactive wastes – the NAS suggested TRU wastes be buried in deep salt deposits. In 1974 a site was found in the southeast corner of New Mexico that met the NAS criteria; construction was authorized by Congress in 1979 and WIPP received its first shipment 20 years later.

WIPP is essentially a salt mine – several miles of tunnels drilled into the remnants of an ancient sea nearly a half mile beneath the New Mexico desert. The salt came from the evaporation of an ancient sea, similar to the Red Sea today; as the sea dried up the salt and other minerals in the water precipitated out of solution, leaving behind a layer of salt nearly 2000 feet thick. What makes this an ideal place for radioactive waste is that salt deposits are dry (salt absorbs any moisture from the atmosphere), salt deposits are geologically stable, and over decades and centuries, salt slowly flows and deforms so that, a century or so, the waste containers will be fully enveloped by the salt, entombing the waste canisters for millions of years to come.

So the idea behind WIPP was to bury the most potentially dangerous radioactive waste in a remarkably stable geologic formation deep underground in an isolated part of the country.

As far as the safety of transporting plutonium and other TRU nuclides goes, these are some dangerous materials and they’re treated with appropriate care. The most dangerous are shipped in sturdy casks called Type B containers – Type B containers are built to withstand impressive levels of punishment; during testing the containers have been immersed in flaming jet fuel, dropped onto metal posts, and run into by rocket-propelled locomotives, all without impairing the container’s ability to safely store the waste it carries. That’s not to say that these containers are entirely without risk – but the risk is mostly from the possibility of a traffic accident involving a large truck carrying a large, heavy, and well-nigh indestructible container.

And then we get to another worry you might have – that they might accidentally put enough plutonium together in one location to cause a criticality or an explosion. Luckily it’s a lot easier to prevent criticality (and even easier to prevent an explosion) than it is to cause one. Much of the reason for this is that there’s not much fissile plutonium in any single container, and the containers tend to be fairly large – this makes it hard to assemble a critical mass of material in the compact volume that’s needed to cause a criticality, with or without an explosion.

But even more than that, plutonium has a number of isotopes, not all of which are fissile. Plutonium-241, for example, is present in large quantities in spent reactor fuel, but it doesn’t fission (it decays to Am-241, which is also non-fissile). Plutonium-238 is also widely used, especially in radioisotopic thermal generators (RTGs) that are used, among other things, to power spacecraft sent to explore the outer solar system. Accumulating large quantities of either of these nuclides might generate enough heat to cause them to glow red-hot, but they won’t start a runaway nuclear chain reaction.

One other thing about WIPP that’s really cool is that some tunnels have been set aside for science. It turns out that being surrounded by hundreds of meters of salt a few thousand feel underground has a way of reducing background radiation exposure. This gives scientists a location with an unprecedentedly low radiation field where they are running experiments in the biology of low-dose radiation exposure, looking for evidence of dark matter, using rare double-beta radioactive decays to tease out the mass of the neutrino, and even exploring the salt formation itself to learn about ancient life.

So let’s see…we’ve talked about the number of shipments, how WIPP was selected and designed, and why it’s safe to transport and bury these wastes in the New Mexico desert. I hope this helps allay your worries – and I hope you can continue enjoying your drives in SE New Mexico! Oh – and if you’re interested, you can take a virtual tour of WIPP at their website (they don’t give tours to members of the general public for reasons of safety and security).