Doc! One of my buddies was telling me that they dropped nuclear weapons near a bunch of beer back in the day, then had a taste testing. I told him he’s an idiot and nukes are too expensive and too dangerous to use for something so frivolous – I got a mental image of some drunk nuclear scientist reaching for the button saying “Hold my beer, man – watch this!” My buddy insists he’s right, but he’s sorta gullible. Did we really do this?

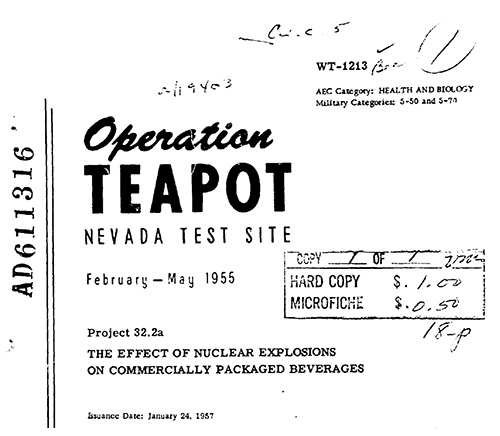

Sorry, dude…but your buddy is right on this one. And believe it or not, the people who came up with this one – part of a 1955 series of 14 nuclear detonations called Operation Teapot – were sober and intelligent scientists and government officials trying to answer some very real questions. The shots in this series of explosions helped test new nuclear weapons designs, some of them using weapons made of different materials, they worked to develop tactics to be used on the post-detonation battlefield, and looked at the effects of nuclear explosions on the society of the day. We’ll get to that last part in a minute, but let me give a little attention to some of the experimentation in nuclear weapons design first.

For example, there was a test of the first nuclear weapon to use U-233 in a composite U-233/Pu-239 bomb core. Today, U-233 is associated with thorium molten salt reactors, and there are a number of factors that reduce its suitability for use in nuclear weapons – but we couldn’t know that until we learned by testing it. That particular bomb released much less energy than expected, disappointing the Army, who had set up a number of test sites to learn about the effects of a 33-kT blast; the 22 kT yield, produced by an experimental core substituted by Los Alamos ruined many of the planned tests. Other weapons design testing looked at the use of different neutron-emitting “initiators,” light-weight implosion systems, the use of deuterium and tritium to boost the yield of a fission weapon, and more – some of which became standard in advanced nuclear weapons designs.

That’s nice and all – but what about the irradiated beer? Why did they even care? Inquiring minds want to know!

Say a nuclear weapon (or two or a dozen) is set off in your city, far enough away so that you and your neighbors survive the blast and, a few days later when you emerge into the remnants of a ruined city, you’re likely to be hungry and thirsty…if not today then when whatever food and drinks you’ve got in your home run out. There likely won’t be city water and water is more important than food. So where are you going to find something to drink?

A lot of us might head for a supermarket or gas station convenience store for bottled water, soda, and beer…possibly with some reservations, wondering if it’s safe to drink. And, thanks to one of the Operation Teapot tests, we know the answer to that!

A few seconds after noon on May 5, 1955 (5/5/55!) the Apple 2 shot lit up the Nevada desert with the light from a 29 kT explosion; outshining the sun even at noon in the Nevada desert. A quarter mile away was a two-story frame house and some other buildings, stocked with food, soft drinks (“pop” if, like me, you’re from the Midwest), beer, and more. The beverages were in glass bottles and metal cans; the goal of the experiment was to see if the containers would survive and whether or not the food and beverages would be changed so as to put people at risk and whether or not the beverages would remain palatable.

Surprisingly, even a scant quarter mile from a detonation twice as powerful as the Hiroshima bomb, most of the cans and bottles survived the blast, although some were damaged by flying debris.

In addition to that, there was some radioactivity induced in the cans and bottles closest to the explosion; the count rate was as high as 4000 counts per minute (cpm) from the neutron activation of sodium (Na-24) in the liquids. Sodium-24 has a relatively short half-life of about 15 hours so its activity started dropping within the first few hours; after three days the activity was down to about 3% of the original activity. As phrased in the report,

“Induced radioactivity…was not great in either beer or soft drinks and would allow the use of these beverages as potable water sources for immediate emergency purposes as soon as the storage is safe to enter after a nuclear explosion…. The beverages themselves exhibited only mild induced radioactivity, well within permissible limits for emergency use.”

Apparently, exposure to radiation also affects the flavor of beer and soft drinks – referred to as “organoleptic changes.” Some of the taste testers said that the radiation made the beverages – especially the beer – taste “aged” or “definitely off,” although much of it apparently tasted more or less normal. That was nice to read, but what I thought was most interesting was that some of the sugars in the sodas was changed from sucrose to dextrose – still sweet, but with a different structure – by the radiation. This is something that normally happens when beverages are stored, but it normally takes several months to happen. Oh – and carbonation was unaffected as long as the container wasn’t damaged!

So – yeah – the US did nuke beer and soda back in the day. But it was for a good cause, and it was nice to confirm that, if the worst comes to pass, we can slake our inevitable thirst, even with irradiated beverages without putting ourselves at risk. And we have the studies to prove it!