Birds of a feather…cluster?

Good morning Dr. Z! So I gotta say I’m a bit worried. Seems there are a lot of folks living around me who had cancer or who have cancer now and for some it’s been pretty bad. Looking things up online it looks like I’m living in a cancer cluster and I’m trying to figure out how to keep myself and my family safe. Can you help?

Boy can I sympathize with you on this one; it can be worrying to see people you’re close to – friends, neighbors, relatives – getting sick, suffering, maybe dying, and wondering if you and your family and friends might be at risk. It’s also normal to try to figure out what’s causing it and how you can keep yourself and those you care about safe. And much of this revolves around the concept of a cancer cluster.

According to the National Cancer Institute “A cancer cluster refers to the occurrence of a greater than expected number of cancer cases among a group of people in a defined geographic area over a specific time period. A cancer cluster may be suspected when people report that several family members, friends, neighbors, or coworkers have been diagnosed with the same or related types of cancer.” The bits I emphasized are the important parts!

For example – every type of cancer has a normal rate of incidence and some types are more common than others. There are a lot of skin cancers (for example), not nearly as many testicular cancers, and very few brain cancers. For this reason, seeing 1% of your neighbors come down with brain cancer would be more alarming than seeing 1% develop skin cancer since brain cancer is so rare and skin cancer so common.

The part about the confined area…seeing 10 skin cancers in a few years on a single block is more concerning than 10 skin cancers in a big city in that same period of time. The bottom line is that cancer is not a rare disease and we expect to see cancers occurring from time to time in any sufficiently large number of people. The question is not “are there people in this group who have cancer?” Rather, the question is “Are there more people in this group who have this specific type of cancer than we’d expect to see in this period of time?” followed by “Have the people with this cancer been exposed to anything that can cause it?” The reason for this is that, not only is the incidence rate different for each kind of cancer, but there are many different causes for cancer as well, and some factors can only cause one or two types of cancer. Take ultraviolet radiation – it’s very effective at causing skin cancer, but it can’t penetrate very far inside the body. So a cluster of seven skin cancers in an area is more significant than an area with the same population in which people have developed two skin cancers, a case of colon cancer, a case of breast cancer, and three cases of prostate cancer.

In your case, you need to see if everyone has the same type of cancer or if there are multiple cancers present. Then you need to see if the prevalence of cancer is higher in your neighborhood than you’d expect to see in a “normal” population. Say you confirmed that most of those who are affected gets colon cancer, which accounts for 7.6% of all new cancer cases, and about 4% of us will develop this cancer over our lifetimes. That means that about one person out of 25 in your neighborhood can be expected to develop this form of cancer. If all or most of the people in your neighborhood who develops cancer is getting colon cancer then that’s very unusual – that might indicate a cluster of colon cancers in your area.

Something else to keep in mind is that, while cancers have a cause, sometimes that “cause” is simply random bad luck – the right gene is damaged in the right way to initiate a cancer. That damage can be caused by exposure to a mutagen such as UV radiation or tobacco smoke, but it can also be a random mutation due to free radicals (chemically reactive molecules) released by our own mitochondria as they power our cells. If there’s an environmental factor – electromagnetic fields or contaminated well water for example – that you suspect is causing the cancers you see then you have to find out if that source is capable of causing the cancers you see.

Not only that, but you should also see that the people with these cancers were exposed to the suspected source. If you’re concerned that, say, contaminated well water is the culprit then you need to ask those who are afflicted if they drink well water; if they’re on city water, if they drink bottled water, if they filter their water, or have some other source of water (or treat their water) such that they’re not exposed to the putative cause then the water they’re drinking didn’t cause their cancer. If few or none of the people with a particular cancer were actually exposed to the putative carcinogen then it’s unlikely that the cluster is real, rather than simply a statistical fluctuation in cancers.

Finally, there should also be some sort of dose/response relationship – areas in which people have a higher exposure to the putative carcinogen (or people who have higher exposure) should have a higher number of cancers – and those with lower exposure should have fewer cancers.

So these are some questions to ask:

- Are the cancers all the same or similar types or a random assortment?

- Is there a carcinogen that cause can the cancer(s) present in the area you’re concerned about?

- Do the areas or people with higher exposure to the carcinogen have higher levels of the cancer?

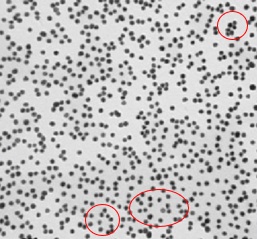

Unless the answer to all of these questions is “yes” then, again, you likely don’t have a cancer cluster so much as random variability in a random phenomenon. What I mean by that…well…picture tossing a few grams of salt or sand on a tabletop. You’ll probably get something that looks like this:

Notice how there are some places where grains are clustered together and other places where there are fewer particles? This is a random variability. The small cluster of grains in the upper left or the lower center is no more significant than the relatively empty space around it. You can’t look only at the clusters and ignore the voids – you must consider them both, and be able to explain them both with your hypothesis – and if your hypothesis can’t explain both then it’s likely wrong.

There’s a story about a man driving cross-country who sees a barn with target circles painted on the side with dozens of shots inside the bullseye. The man stops at the farmhouse, walks up to the door and knocks and, when the farmer answers the door the man compliments him on his marksmanship, asking how long it took him to become so proficient. The farmer laughs and says “Oh, I just took a bunch of shots at the barn and then painted the bullseye where I had the most bullet holes.” An epidemiologist I talked with several years ago used this story to explain cancer clusters – many of them are “recognized” the same way the farmer “hit” the bullseye – by looking at a random distribution of cancer cases and investigating only the clumps, but not the voids. That’s why we need to do more than just look for the clumps – but to question then and try to understand them as well rather than go with our gut feelings.