Doc! What’s this I hear about microbes traveling through space? Do we need to worry about a real Andromeda Strain? Not to mention, are we all Martians – or even Alpha Centaurians?

This is a really interesting question, and the answer gets into some interesting science. The short answer is “Maybe” to all of your questions – but with different odds for each of those “maybes.”

To start, space is a horrible environment for life like us – we need air, gravity, water, food, temperatures more or less between boiling and freezing (with some exceptions), moderate to low radiation levels, access to the nutrients life requires, and more. Vacuum, extreme temperatures, lack of gravity, radiation, lack of food – that’s what space seems to hold. But here’s the thing – scientists have found live Earth organisms that have survived in space for months to years.

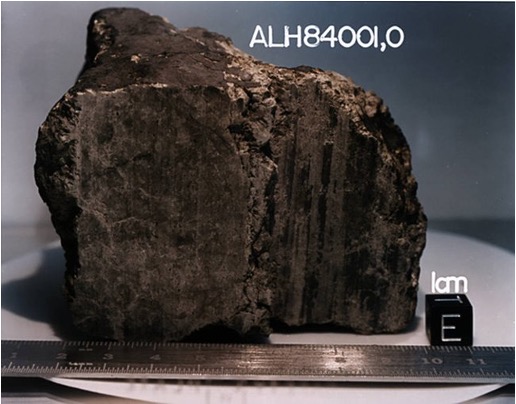

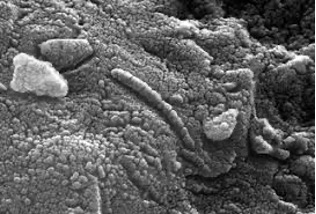

That’s pretty impressive – and hats off to the microbes and fungi that have managed to eek out a strategy for survival in an environment that would kill most living organisms in a few minutes. But we need to realize that it took a rock blasted off the surface of Mars more than ten million years to reach the Earth – and compared to the distances between stars, Mars is closer than next door; it’s in the apartment next to ours. So, while it’s impressive to see microbes living for up to a few years in the harsh environment of space, that’s only scratching the surface when it comes to living organisms being transported from star to star.

Here’s the thing – in any location in our galaxy, on average, there will be an exploding star close enough to expose any organisms to a possibly fatal dose of radiation every few to several million years; this means that the Martian meteorite was probably irradiated multiple times while it was making its way from Mars to the Earth. Rocks travelling from star to star will be blasted even more times. And unless microbes are buried deeply enough in the rock to survive this onslaught they’re probably going to die long before the rock can reach another star.

So picture a planet somewhere off in the reaches of space, and the planet has oceans teeming with bacteria and algae – just like the Earth for most of its history. At some point a small asteroid slams into the planet, creating a crater and blasting thousands of tons of the planet’s rocky crust, much of it saturated with bacteria and algae, into space. Most of this material falls back to the planet; some escapes the planet’s gravity, and some has enough energy to escape the star’s gravity. The rocks that escape from the star entirely – these are the ones we need to follow as they drift through space towards another star system…ours. So let’s think about one – a rock that’s maybe a few feet across.

Now this next part is kind of neat – the way that the incoming radiation kills microbes is by knocking electrons off of atoms; this is the ionization process and the electrons are called secondary electrons. These secondary electrons are what would kill any living organisms trying to hitch a ride. What makes it neat is that this is the same phenomenon taking place inside me during my radiation therapy – the medical physicist was trying to design a therapy session in which these secondary electrons would reach the maximum dose at the depth of my tumor. The photon (x-ray) radiation passed through the outer layers of my body creating ionizations and the secondary electrons cause further ionizations (along with photons that hadn’t yet interacted) with radiation exposure increasing to a maximum at some depth and then dropping off again. In the case of our microbe-infested rock, by the time it reaches us it might have been exposed to sterilizing doses of radiation tens or hundreds of times. By the time it reaches us, it’s likely to be pretty well sterilized. It might shower our planet with amino acids (those that survive the fiery descent) or with other elements and compounds that would help life to form here. But anything that was living inside that rock when it was first blasted into space – that’s all going to be dead. But what about something larger – or something smaller?

The larger a rock is, the more shielding it provides and the more microbes are likely to survive. The thing is, there are a LOT of small things – pebbles, grains of sand, dust grains – in the universe and not nearly as many big things. With the large things – boulders to asteroids – microbes can shelter inside and the objects are usually large enough to keep the interior safe through shielding from radiation, but also cool enough for microbes to survive the flaming atmospheric entry. The problem is that there’s just not many large rocks compared to smaller ones. But what about the billions of sand-sized grains and the trillions of dust-sized grains? It turns out that the smallest grains (which are still large enough to house millions of microbes) might just be the most hospitable due to being so small that the radiation passes through them without generating enough secondary electrons to sterilize the grains. Sometimes smaller is better.

So let’s get back to your questions!

Can microbes travel through space? Maybe. We’ve seen evidence that single-celled organisms can survive in vacuum, can withstand incredibly low temperatures, and can survive high levels of radiation – the question is whether or not life can survive all of these simultaneously during transit times of tens or hundreds of millions of years.

Do we need to worry about an actual Andromeda Strain? It’s hard to tell – the only accurate answer at the moment is “maybe; maybe not.” At the moment we know of exactly one type of life – what we have here on Earth – and we have no idea if other life even exists, let alone if it shares or can somehow disrupt our biochemistry. And until we find living organisms from somewhere else we can’t answer this question.

Are we all Martians or Alpha Centaurians? This is “maybe; probably not” – “maybe” because, again, until we have a chance to compare our genetics and biochemistry to that of life from somewhere else we just don’t know. And “probably not” is because of all the difficulties already mentioned.

So I guess I just took over 1000 words to tell you “I don’t know.” On the bright side, at least I explained (I think) why that’s the answer at the moment, but that it might change at some point, if we ever find (or meet) living organisms elsewhere in our solar system or around another star.