Hey Dr. Zoomie! Hope you’re back from your astronomy conference; I saw something a little more down to earth I wanted to ask you about. I saw an article recently about the Olympic surfers being exposed to radioactivity from nuclear testing in the past. What???? Can you tell me what’s going on and if any of the surfers were at risk? Thanks!

I got back a few days ago – a 15-hour flight followed by Customs and Immigration, and then another three hours back home from there. That’s a lot of time in the air, but the trip was worth it!

As to the surfers…we saw some serious waves at the Cape of Good Hope, but I’m not sure they were surfable. Oh, and with the radiation exposure – yeah – that sort of begs for an explanation, doesn’t it?

It actually starts in the 1960s when France, like the US, UK, USSR, and China, was testing their nuclear weapons. Like the other newly nuclear nations, France’s first tests were done above-ground; unlike most of the other nuclear powers, France continued atmospheric nuclear weapons testing past the date of the atmospheric nuclear test ban – they set off a total of 41 atmospheric explosions, the last taking place in 1974. Of these all but four were detonated at the Moruroa Atoll (the other four were set off at the Fangataufa Atoll) in the South Pacific; Tahiti is just about 750 miles to the northwest of the French testing site.

Fallout from one test – a 4 kT explosion set off in 1974 – was carried almost directly over Tahiti, exposing the inhabitants and depositing radioactivity onto the ground and in the surrounding waters. In the intervening decades there has been a tremendous amount of controversy regarding the long-term impact of this testing on the health of the inhabitants of various islands in the area.

I’m not going to try to adjudicate the past claims or to second-guess any of the dose measurements and calculations made by French scientists over the years; with only a few snippets of information I can’t really do more than make an ill-informed guess. But I would make a few comments to consider, with regards any stories you might hear or read involving radiation and its health effects (there are three related to the French nuclear testing and Olympic surfers – the one linked to in the question, this article in the journal Science, and this report by an independent group):

- Cancer is not a rare disease, striking at least 40% of us in developed nations and killing at least 25%

- It’s not possible to look at any individual cancer and determine whether or not it was caused by radiation exposure; the best we can do is to determine the likelihood of a cancer’s being radiation-induced based on the dose we calculate,

- Or we can look for “extra” cancers in an exposed population to see if there’s a statistically significant increase over what we expect to see.

- The single most important piece of information to have when determining the probability that a cancer was caused by radiation exposure is the dose to the site of the tumor. Without that information we can’t come to any meaningful conclusions.

- It’s also worth bearing in mind that some tissues (e.g. the thyroid) are more sensitive to radiation than others (e.g. the brain).

Now, on to our Olympic surfers! How much risk did they face as they rode the waves off Tahiti and during their stay on the island?

According to the article in Science, a new simulation of the radioactive plume shows that the dose to the island’s inhabitants might have been roughly twice as high as what was calculated by the French government, which had previously concluded “that people on the island received a dose of about 0.6 mSv” from the 1974 test; this means that dose to the residents might have been somewhat in excess of 1 mSv (100 mrem) when including radiation dose from the ingestion of contaminated food.

So let’s see what this means for our surfers 50 years later.

First, let’s consider what nuclides we’re concerned about. In 1974 the most important nuclides were the radioactive iodines since they’re easily absorbed into the body and collect in the thyroid, a radiation-sensitive organ. But the most commonly-produced iodine nuclides formed have relatively short half-lives and none of them are left after a half-century. The longest-lived nuclide that would travel so far and would be produced in relatively large quantities is Cs-137, which has a half-life of about 30 years. After 50 years of decay the original Cs-137 is down to about 30% of the original level. This means that if we make a worst-case assumption that the 1.2 mSv (120 mrem) in 1974 was due entirely to Cs-137 then the highest dose to the surfers today would be around 36 mrem (0.36 mSv). And that’s if the surfers spent enough time to maximize their exposure, which would require eating contaminated foods and walking on contaminated ground for extended periods of time. So the 36 mrem is clearly an upper estimate. But let’s see what that’ll do.

To start, that’s about a third of the allowable annual exposure to members of the public. It’s about the dose of a few medical x-rays and is in the ballpark of the dose picked up by the surfers as they flew from their home countries (for the ones from Europe and North America, anyhow) to Tahiti. And it’s less than 1% of the lowest dose for which there’s enough epidemiological data to justify calculating a formal risk estimate (the Health Physics Society recommends against trying to calculate risk for any dose of less than about 5 rem – 5000 mrem – in a short period of time or less than 10 rem over a lifetime).

The other thing to consider is that the surfers will only be exposed to radiation during the time they’re on land; water is a pretty effective radiation shield. So here, too, using the corrected numbers developed by the French is clearly an overestimate and the actual dose will be somewhat lower.

The bottom line is that it’s entirely possible that the surfers were exposed to small amounts of radiation due to fallout from the 1974 French nuclear test. But the dose is so low, even using worst-case assumptions, that it’s not likely that it’s going to cause them any harm. Or, put another way, the cost of traveling to Tahiti might discourage me from traveling there – but the potential radiation exposure would not enter into my decision-making.

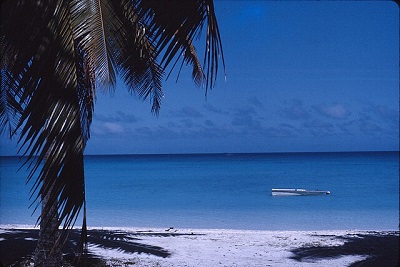

Image Reference:

- Mururoa_lagon.jpg

- Author: Georges Martin