Greetings, Doctor! I was reading an article a few months ago that our planet was recently blasted by the “brightest gamma ray burst of all time” and that it “seared the atmosphere” and more dramatic statements. This sounds fascinating – it also sounds a bit worrisome. I started digging around and found a paper by an astronomer who feels that a nearby gamma ray burst might have triggered a mass extinction. I have to admit that it’s still sounding a bit worrisome and I was wondering if you can tell me if my concerns should be acted on or if they’re groundless. I appreciate any information you can provide.

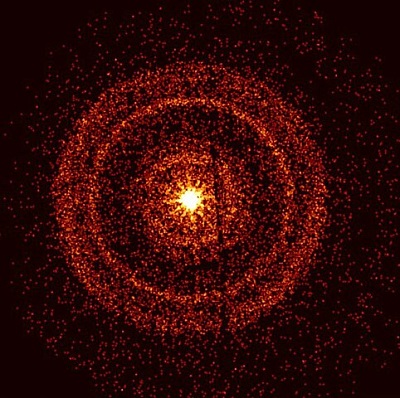

Ah – exploding stars and gamma rays of death – it just doesn’t get any better than that, and what a great way to start my weekend! And – boy – there’s so much we can get into as well; astrophysics, radiation health effects, atmospheric photochemistry, and death on a global scale…sounds like time to roll up the sleeves, break out the calculator, and let’s have some fun. Oh – and I think you’re referring to a burst that was detected on October 9, 2022.

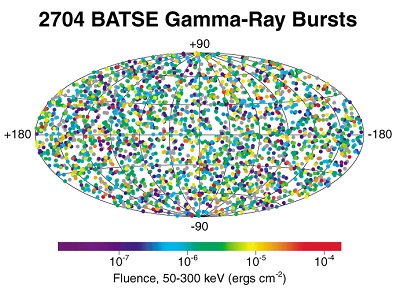

Before we get into the nitty-gritty, though, a little history! The first gamma ray burst (GRB) was detected by a Vela satellite that was lofted into orbit to look for signs of nuclear weapons testing; on July 2, 1967 the satellite picked up a burst of gamma radiation that couldn’t be correlated with any other indications of nuclear testing – after eliminating all other possibilities, the most likely explanation was that they were coming from the cosmos. Further detections of additional events showed they were scattered more or less randomly across the sky and proved they weren’t taking place in our stellar neighborhood or even in our galaxy – they were coming from billions of light years away.

A breakthrough came when astronomers were able to link a burst of gamma rays with a visible object for which they could measure a distance; when astronomers calculated the energy arriving here on Earth and corrected for that distance they realized that gamma ray bursts are the most powerful events in the universe since the Big Bang – as much as 100 times as powerful as a “garden variety” supernova.

In recent years astronomers and astrophysicists have made a lot of progress in figuring out what causes these things – colliding neutron stars or a neutron star being absorbed by a black hole are the two most likely candidates for short-duration (less than a few seconds) GRBs; longer-duration events, lasting for minutes to hours, seem to come from the collapse of massive stars that are in the process of forming black holes. Part of the power of these explosions seem to come from the massive scale of the events that cause them – neutron stars weigh a few times as much as our Sun and when two of those collide, or when one gets ripped apart by a black hole, the energy from that collision provide a lot of power. But it seems likely, too, that part of the magnitude of these explosions might be partially due to geometry – specifically, much of the energy that’s released seems to be expelled in two relatively narrow beams. If 100% of the energy is focused into two opposite beams that are only a few degrees wide (about 1 or 2% of the total area available) and if one of those beams is aimed at us then the explosion will look far more powerful than it actually is. They’re still tremendously powerful – maybe just not quite as powerful as they look at first glance.

With the whole atmosphere-searing thing…that’s maybe a little overly dramatic, but it’s not completely without foundation. Gamma rays are ionizing radiation so when the gamma rays slam into the air these will do what gamma rays do – they add enough energy to the electrons that absorb them to strip them from the atoms, creating ion pairs. The amount of ionization that occurs will depend on the number of gamma ray photons that strike the atmosphere and their energy. More gammas that are packing more of a punch will create more ionizations – sometimes enough to interfere with communications and electronics. On the other hand, it’s not enough energy to, say, cook a steak. So I guess whether or not that constitutes “searing”…I’ll let you reach your own conclusion on that one.

And that brings us to the really fun stuff – whether or not a GRB can kill all life on Earth. The October 9, 2022 GRB made a measurable impact on our ionosphere, but it wasn’t in the “searing” category and it didn’t expose any of us at the surface (or traveling by air) to a harmful radiation dose. But that GRB was nearly two billion light-years away. Makes you wonder what kind of impact it’d had if it was closer. For example, if it were a “mere” 1 billion light-years away it would have packed four times the punch and at a paltry 10 million light-years away, on the other side of our Local Group of galaxies, it’d pack 40,000 times the wallop. One final superlative – I calculated that a GRB in the Andromeda galaxy, nearly three million light years away, would produce a fatal dose of radiation to anyone in space anywhere in our galaxy – luckily we live at the bottom of an atmosphere, which provides enough shielding to reduce that dose to easily survivable levels to any organisms on our planet’s surface.

Using the inverse square law we can keep this up, finding a distance at which the amount of radiation penetrating through the atmosphere to reach the surface will be enough to be fatal. So – sure – a GRB can be fatal if it’s close enough. But then there’s another part of the question –we detect about one GRB across the entire visible universe per day; there are far fewer stars as we look closer and closer to home and nearby GRBs occur far less frequently. Estimates are that our galaxy likely only hosts a GRB once every 100,000 years or so (within an order of magnitude – the average interval could be as short as 10,000 or as many as a million years). The thing is, unless the beam is aimed our way we’re not going to see it and it can’t affect us – hence the large error bars on the estimated interval.

One astrophysicist estimated that a GRB can dump enough energy into an object (a planet, for example) to vaporize it from as far away as 200 light years – that would certainly cause a mass extinction, but if Earth had been vaporized then we wouldn’t be here to discuss the matter. So it seems safe to assume that’s never happened. Out to about 8000 light years, a powerful GRB can deliver enough energy to deliver a lethal dose of radiation at the Earth’s surface, but those don’t happen very often – perhaps once every several hundred million years. So a GRB that’s close enough to Earth can kill organisms at the surface – but have they?

With the gamma radiation, let’s start with the “burst” part of the name – most GRBs last for only a few to a few tens of seconds. This means that they can only irradiate half the planet and can “only” kill half the life on Earth – at the most. That would be a GRB over the equator; a GRB that exposes the polar regions wouldn’t be nearly as lethal. Having said that, we can also ask ourselves if killing half the life on Earth might be sufficient to cause ecosystems to collapse around the world. I honestly don’t know – I can make a plausible case for both “yes” and “no,” so I guess I’d have to come down on “maybe.” But there’s more going on than just gamma radiation, so let’s see what else might be happening.

In 2004 Adrian Melott, an astrophysicist, was the lead author on a fascinating paper that explored the possibility that a GRB might have caused one of five mass extinctions that have occurred over the last 500 or so million. Melott knew that, a few years earlier, other astrophysicists (John Scalo and Craig Wheeler) had looked into how the ultraviolet (UV) from a nearby supernova might affect our atmosphere – they found that a blast of UV was likely to destroy our ozone layer as well as initiating photochemical reactions producing a smog layer that would block the sun across the face of our planet, dropping temperatures and possibly triggering a global ice age.

Melott realized that GRBs would likely produce UV as well as the gamma radiation, and that the gamma and x-ray radiation instigate these photochemical reactions as well. Not only that, but when Melott and his eight coauthors started thinking about how a GRB-caused mass extinction might look in the rocks and fossils, they realized that the Ordovician extinction was a reasonable fit. Their model of such a mass extinction included:

- A loss of UV protection, for example, would be fatal to organisms living in the uppermost layers of the water column but deeper-dwelling organisms would survive – which is what the fossil record shows.

- The cooling caused by photochemical smog could launch a glaciation…such as the few million years of cooling leading into the brief Hirnantian glaciation in the late Ordovician.

- Lack of an iridium layer and other indications of an asteroidal impact – which might be present, but has not yet been observed anywhere in the rock record.

A nice indicator of a nearby supernova is the presence of supernova-produced radioactivity such as iron (Fe-60) and plutonium (Pu-244), but if a GRB triggered the Ordovician extinction it could have been thousands of light years away, rather than the few hundred light years for a supernova that would have the same impact. At so great a distance the number of radioactive atoms would be so dilute and would have undergone so much decay that failing to find these can’t be used to prove or disprove anything. The bottom line is that there are indications pointing in the direction of a GRB as the cause, but there’s no definitive proof. Not yet.

So, getting back to your question…. A nearby gamma ray burst could cause problems for us on Earth, and could even trigger a mass extinction if it’s within several thousand light years. A far more distant GRB would be able to kill astronauts who are beyond the protective shielding of our atmosphere. But luckily these sorts of things don’t happen very often – maybe only every hundred million years or so! Which makes GRBs an occasional problem for our planet – but not much of a risk to you or me.