A while back I wrote about various uses of external and internal radiation in medicine; for this piece I thought it might be interesting to share my own experience on the receiving end of the beam. And before getting into the details, I need to note that my cancer was not life-threatening; the idea was to take care of it before it got to that point. I should also note that I’ve had friends and relatives whose cancers and subsequent radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy were much worse than mine – some who underwent multiple surgeries, some who succumbed to their cancer. I’ve been lucky.

One other thing I should mention is that it was over five years between being diagnosed with prostate cancer and beginning treatment and that I did not have any symptoms at any time; in fact, if my cardiologist hadn’t recommended having a PSA test it would likely have taken a few more years for me to know that I had cancer. And then, for nearly five years, my urologist and I kept track of it through regular PSA tests, an annual MRI, and the occasional biopsy, until my last biopsy, a few months ago, showed the cells had changed in such a way as to increase the risk of spreading. So I spent some time discussing the options with a surgeon and with a radiation oncologist, and after considering what each entailed, the potential side effects, the recovery period, and so forth, I decided to go with radiation therapy.

A brief pause for some numbers. I spent some time talking with the radiation oncologist and the medical physicist who planned my treatment, as well as bringing some of my own radiation instruments in during therapy sessions and some of the numbers are sobering. For example:

- Dose rate in the radiation beam is 844 rad/minute

- Dose to the prostate each session is 250 rad

- Dose to the prostate over 28 sessions is 7000 rad

- Dose to me (approximate) during each treatment is around 300 mrad (including the initial imaging CT)

- Dose to me (approximate) over 28 sessions is 8-9 rads

Now let me back up a little to explain what these numbers mean and where they come from, as well as putting them in context.

There are two goals in most radiation therapy – 1) deliver enough dose to destroy the cancer cells while 2) sparing healthy tissues as much as possible by minimizing the dose they receive. And here’s the short version as to how this is accomplished:

- Preparatory visit #1 – the oncologist injected some gel in the space between the prostate and the rectum to push the radiation-sensitive tissues of the rectum away from the tumor, minimizing the dose it receives. In addition, three small gold markers were injected into the prostate to help the computer adjust each exposure to account for any small changes in the position of the prostate from one exposure to the next.

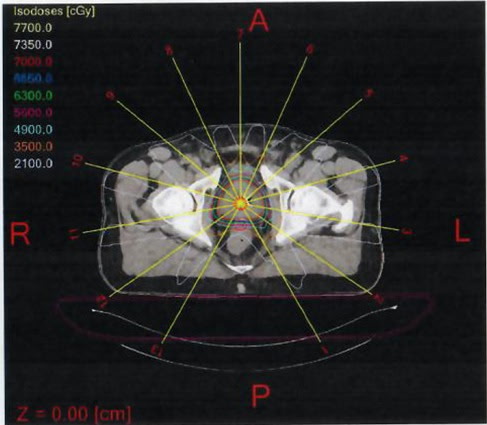

- Preparatory visit #2 – I headed to Radiology a week later for a CT scan; the scan was taken with me in the same position in a CT machine identical to the one to be used during the therapy sessions; the medical physicist and radiation oncologist used this CT to simulate various treatment setups and select one that gave the target dose to the tumor with minimal dose to surrounding tissues

- The goal was 250 rads per treatment session to the tumor and a volume surrounding it (to account for possible movement of the tumor during the treatment) with minimal dose to nearby healthy tissues

- The goal was 250 rads per treatment session to the tumor and a volume surrounding it (to account for possible movement of the tumor during the treatment) with minimal dose to nearby healthy tissues

- During treatment, using multiple exposures (13 in my case), each from a different angle and all focused on the tumor to give the tumor the full dose while each exposure pathway receives only about 20 rads per treatment

- And using a multileaf collimator – in the machine I’m being treated in, there are two overlapping collimators, each leaf of which can be repositioned from moment to moment to adjust the radiation dose received by every square millimeter of the area(s) being exposed from second to second.

So that’s what’s happening with the exposures and the machine – here’s what I experience.

- I wake up at about 5 AM, shower, dress, have some coffee and a bite to eat, and try to have a bowel movement so I can show up with a full bladder and empty rectum. On my way out the door between 5:45 and 6 I grab a bottle of water or iced tea to drink in the hour or so I’ll be on the train from Brooklyn into Manhattan. Two or more trains (depending on whether or not I can catch the express trains) and an hour or so later the MTA spits me out onto the street corner across from the hospital on the Upper East Side.

- At 7 (or so) I cross the street, walk into the hospital, go down a flight of steps to Radiation Medicine, make a cup of coffee (gotta continue the bladder prep!), and wait until it’s my turn. When my call comes I go to the changing room, remove my pants and underwear, put on a gown, and wait to be called to the LINAC room. I’ve pretty much memorized the two magazines in the waiting room, but they’ve got nice photos so I leaf through them both again until I hear my name called from down the hallway.

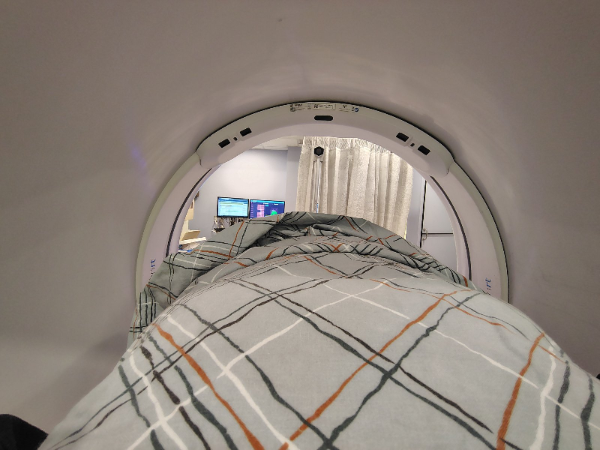

- Around 7:30 I wander down the hallway, holding my gown closed behind me to avoid accidentally mooning anyone (if I moon somebody I’d like it to be deliberate!), and navigate a few turns to get to the door to the accelerator vault. The hallway turns are deliberate, by the way, to keep from giving radiation from the linear accelerator a straight path to reach the waiting rooms – with this setup it’ll have to go through a few walls, each of which reduces the radiation exposure a bit. I walk past a thick door (shielding for those outside) and wait a moment while the medical folks finish setting up the table for me to lie down on. I take my place, they put a blue foam ring around my feet to keep me from moving my legs (actually, the position of my prostate), give me another ring to hold with both hands on my chest (this time, to keep me from reaching down to scratch). At the same time, they’re adjusting the position of my body ever so slightly, using lasers, visual marker on my hips, and a machine vision system – the goal is to have me in the exact same position on the table every single time to increase the odds that my prostate is in exactly the same location and in exactly the same orientation every single time I’m irradiated. That done, everyone (except me) leaves the room and the thick door closes, protecting them from the radiation (because they don’t have cancer and they handle many patients daily) and the table raises up a little and positions me inside the LINAC.

- Around 7:35 (or so) I hear a soft buzzing – that’s the imaging CT. What it’s looking for is the three gold markers the radiation oncologist implanted during the first prep session. Using those markers as reference points, the computer calculates the final adjustments to bring my prostate exactly into the right position. I hear a slight whir as the motors are energized, the table gives a small jerk to the left, a somewhat longer movement towards my head, and stops. I’m glad because it means I did OK on my part of the prep – if my bladder wasn’t full enough or if my rectum was protruding into the full-dose region I’d have been asked to wait longer (to let the bladder fill) or sent to the bathroom to try to move my bowels (for the rectum). But once the table moves, the treatment will soon begin.

- Around 7:37 (or so) I hear a louder buzzing – usually from below me and to the left. I’m not sure what it is – I know it’s not the beam itself since the shots come from above – maybe a power supply? Or the radiofrequency radiation generator that produces the radio waves that accelerate the electrons to high energies? In any event, the sound lasts about 6 or 7 seconds and it lets me know the treatment has begun. That’s repeated another dozen times – 13 shots in all, each lasting between (I think) 4 and 10 seconds and each delivering about 20 rem to the tumor. The reason that the duration varies is that each shot is passing through a different thickness of, well, me to reach the tumor; when there’s more of me for the beam to pass through it needs to last a bit longer to equalize the dose. After the 13th shot the table gives a few small lurches to return me to the center of the machine, moves in the direction of my feet to extrude me from the ring, and lowers itself down. As I’m trying to wriggle the ring off my feet the thick door is opening and the staff are coming into the room to take the rings, make sure I safely dismount from the table, and see me back to the changing room.

- And, I should add, I don’t feel a thing the whole time, I don’t get a metallic taste in my mouth, I don’t see flashes in my eyes, and I don’t smell anything (although the medical physicist tells me that some patients report smelling a whiff of ozone from the ionization of the air).

- And, I should add, I don’t feel a thing the whole time, I don’t get a metallic taste in my mouth, I don’t see flashes in my eyes, and I don’t smell anything (although the medical physicist tells me that some patients report smelling a whiff of ozone from the ionization of the air).

- By 7:45 (or so) I’m headed out the door, out of the hospital, and down into the subway station. Three trains and 20-30 minutes later I’m walking into my office where, ironically, I work as (among other roles) Radiation Safety Officer, striving to keep everyone there from receiving even a fraction of the 300 mrem I’ve now received during each of 28 treatments (the annual dose limit for all but a few of the staff at my workplace is 100 mrem annually).

- Longer-term…today was the last of my 28 treatments. Thanks to the multiple beams, no single part of me has received enough dose to give me skin burns, so that’s not an issue. The 300 mrem per session and 8.4 rem over the last 5+ weeks aren’t nearly enough to give me radiation sickness, although my hematologist told me that some of my blood cell counts have dropped a little, possibly due to the radiation exposure. I’m exhausted most days – a lot of that is from waking up at 5 AM, but the radiation oncologist tells me that some is likely from the radiation exposure. And the radiation has irritated my bladder and urethra (so I have to pee more often and it’s painful, as though I have a urinary tract infection). But really, I can’t complain – of the people I’ve known who have had to undergo radiation therapy, I’m getting off easy.

One other thing is the hormone therapy – technically it’s a type of chemotherapy, but it’s not the harsh chemo most people think of when they hear the word. First, what the hormones do is to make the cancer cells more susceptible to the radiation – I started about two months before starting the radiation and will continue for a total of six months. And, of course, there are side effects, the most annoying being hot flashes. But I’ve had friends who have gone through difficult chemo – hot flashes aren’t a big deal, especially not when compared to what so many others have to go through.

Aside from all of that, I’d like to mention that the people I’ve been seeing every day – staff and patients alike – have impressed me more than anything. The patients are matter-of-fact. They’re not complaining, they’re not whining, and they’re not crying – each one of them, regardless of what might be going through their heads, is simply keeping their composure and their dignity as they go through a very trying part of their lives.

And with the medical folks, where do I begin? I’m grumpy and undercaffeinated when I walk in the door around 7, while they’ve all been working for some time already. And yet they’re invariably cheerful, welcoming, and working efficiently, and they treat us professionally, compassionately, and respectfully – in addition to being nice people. I know I’d get the same radiation dose no matter how nice they were, and I’d have the same chance of a cure – but it certainly makes everything go more smoothly and more easily for all of us. And the same for the others involved in the treatments as well – the medical physicist was more than willing to spend time answering my questions and walking me through her treatment planning process, the radiation oncologist and his nurse practitioner also did a great job of talking through what the radiation therapy would entail. And, of course, my urologists – the first, who diagnosed my prostate cancer and went through most of the “watchful waiting” period and the second, who inherited me when the first retired and, one Friday evening, instead of turning off her office lights and heading home for the weekend, called me to discuss my biopsy results and what they meant – they both helped me to understand what was going on, what the various test results meant, and giving me the information I needed to make what I felt was the right decision at every step.

Anyhow – that’s where things stand at the moment, although I imagine there will be new information as the doctors track the (hopeful) shrinkage of the tumor over the next several months. And if there’s anything that seems important enough to share, good or bad, I’ll post an update.