Hey Doc – I liked reading your piece about small modular reactors, but then I saw this article about that we can’t even take care of the nuclear waste made by the reactors we had 50 years ago! If we really build all these new reactors, how can we even hope to find a place to put all the waste they’re going to produce if we can’t even handle what we’ve got?

In the 1990s I was briefly involved in an effort to find a location for radioactive waste disposal facility. One of the first steps was to ask for towns and villages to volunteer to host the site. Want to guess how many stepped forward? Crickets. Not a single volunteer, even when they were told about the money and jobs that would be generated. Can you believe that not even the poor areas wanted to host a radioactive waste dump facility? In case you’re wondering, I am being a bit facetious here – there were a few people involved in the process who were genuinely surprised, but there would have been a lot more surprise if any town or village had stepped forward. And I can understand that – people just don’t know much about radiation and radioactivity except for the over-the-top hyperbole put out by the anti-nuclear power folks. Of course nobody wants to host a radioactive waste facility.

Before going on, let me clarify one point – the difference between radioactive waste and spent reactor fuel. I’ve generated – literally – hundreds of tons and tens of thousands of cubic feet of radioactive waste and the vast majority of it was soil with small amounts of thorium or radium. The rest was mostly paper towels, laboratory glassware, latex gloves, and the like. In the 40 years I’ve been producing radioactive waste there’s only been one item that was potentially hazardous – a piece of metal made radioactive by exposure to neutrons in a nuclear reactor. And in all that time, I have not generated even trace amounts of spent reactor fuel. What we’re talking about here is spent reactor fuel – the fuel rods that no longer have enough U-235 to continue producing useful amounts of energy and that can be dangerously radioactive when first removed from a reactor core, but that decay away over time.

Here’s the thing – we’ve been producing spent reactor fuel for 80 years and, in spite of some early missteps, we know how to safely transport and dispose of the stuff. And not only do we know how to dispose of spent reactor fuel, we even know where we can put it. I’d go as far as to say that spent reactor fuel disposal does not pose any insurmountable scientific or technical problems – the problems are almost entirely political and societal.

Here’s what we need to do, as a society, to safely dispose of spent reactor fuel:

- Safely transport it to the disposal site without exposing the public to excessive amounts of radiation

- Store it in a safe and secure location

- Protect the public and the environment from the possibility of release of dangerous amounts of radioactivity

- Convince the local, state, and federal governments to pass the necessary legislation.

I won’t go into the safe transportation part of this except to say that we routinely transport high levels of radioactivity around the country and around the world without incident. I’m pretty sure I’ve seen more television time devoted to fictional transportation accidents than to real ones. And I’ve made measurements myself on spent fuel casks, noting that radiation levels were quite safe.

Finding a safe and secure location is a little more complicated, but it’s eminently doable. According to the EPA there are over 1145 hazardous waste treatment and disposal facilities in the US; in addition to these there are a number of low-level radioactive waste facilities scattered around the US (some currently accepting waste and some not) as well as a few sites where the reactor compartments of retired nuclear submarines and other former military reactors have been buried, some for decades, without incident. And – yes – I know that there have been leaks and contamination from radioactive waste disposal sites (Hanford, Savannah River, and the UK’s Sellafield sites come to mind), all of which date back over a half-century and all of which pre-date current landfill designs and requirements.

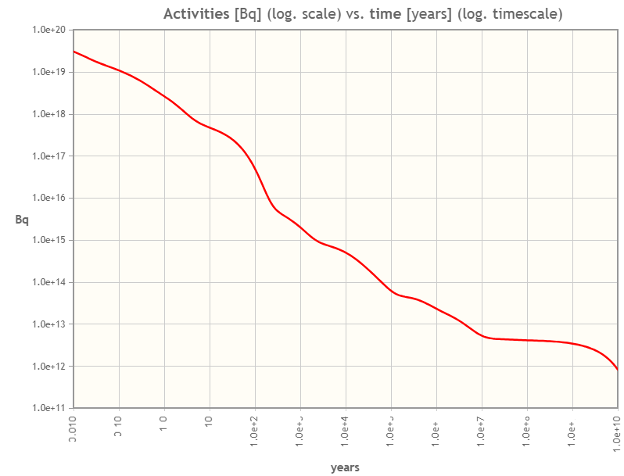

I’ll go out on a limb and say that there is no “best” location and no “perfect” disposal site. No matter how ideal a location might seem, someone will always be able to find a flaw or suggest a different location that’s just a little better. But the thing is, we don’t need to find a perfect location, or even the best location – all we need is a location that will keep harmful levels of radioactivity from leaking into the environment for centuries to millennia. But it’s also an amount of time we can sort-of relate to. I’ve walked the aisles of churches and cathedrals older than that; I’ve stayed in hotels older than that; I’ve visited temples and aqueducts and other buildings older than that. The Ancient Egyptians, the Khmer, the Ancient Romans, the Incas, and a number of other ancient civilizations could have constructed a repository capable of protecting spent reactor fuel for the millennium or two during which it poses the greatest risk, especially considering that 99% of the radioactivity will be gone after the first century. When we consider that the waste will be sealed within sealed cannisters buried deep inside rock far from any population center with several layers of monitoring to detect even trace amounts of leakage, it seems we can meet the third set of criteria noted above.

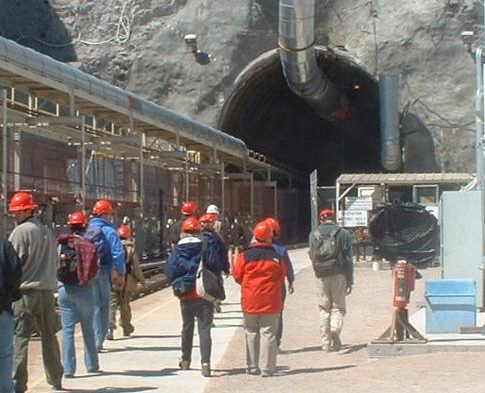

But then we come to the fourth criterion. Here, the thing is, Congress designated a national disposal site over 20 years ago, tunnels were excavated…and the project was shut down. And while there were some scientific and technical reasons raised against the site, those objections could be addressed. What did it in was political and public opposition. Thus, we find ourselves storing spent reactor fuel at more than 50 “temporary” sites around the nation, at the various nuclear reactor sites. And, as new reactors come online and begin to refuel, unless we can find a way past the political and societal impasses, it’s likely that we’ll continue to store spent reactor fuel at the various nuclear power stations around the country while we continue to hope that something more permanent can be devised.

I’d like to make two final observations, if I may.

First is that waste produced during fossil fuel extraction and power production contains radioactivity, and producing energy using fossil fuels gives more radiation dose to the public than does nuclear power production owing to the natural radioactivity they contain.

Second is that our civilization is using ever-more energy as the developing world raises its standard of living and as the developed world raises its use of power-hungry computing. We need to choose – do we try to keep most of humanity in poverty and deny them access to the technology we enjoy; do we, ourselves give up much of what we’ve grown accustomed to (streaming cat videos, AI, cloud computing); do we meet the need for more energy the way we have in the past, with fossil fuels and a hodge-podge of other technologies while hoping that global temperatures slow their creeping upwards; or do we try to build more nuclear power plants and hope we figure out the whole spent reactor fuel thing. Somehow, I think that streaming cat videos and (maybe?) nuclear reactors will win.

Header Image credit: Daniel Mayer, Tour group entering North Portal of Yucca Mountain (25 March 2002). Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0,

Header Image reference url:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tour_group_entering_North_Portal_of_Yucca_Mountain.jpg