Doc! What’s this I hear that the CIA was setting up a nuclear battery (or something) for spying on China and lost it and now it’s going to pollute some rivers in India? Is this for real?

Well…yeah…that sounds about right, with a few caveats. One caveat has to do with environmental contamination; the other is that, while there might well have been small amounts of Pu-239 (which is used in nuclear weapons) present – more on this later – the primary nuclide present was Pu-238. But the main part of the story – hauling a bunch of plutonium to the top of one of the world’s tallest mountains to power a listening post – that part rings true. Now let’s back up a bit and look at some of the details.

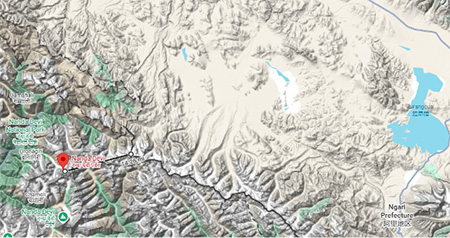

In 1964 China detonated their first nuclear weapon at the Lop Nur site in western China. The test was a surprise, largely because it was difficult to get human intelligence inside of China; because of this the CIA decided to see if they could see (or listen) into China by putting an observation post on a high mountain close to the Chinese border to eavesdrop on communications between missiles being tested and their ground station. The location chosen was Nanda Devi, a high mountain (25,645 feet tall) less than 20 miles from India’s border with China. Putting together a team of American and Indian mountaineers, agents, and soldiers, along with over a dozen of the ubiquitous Sherpas, Spending some of the summer months in training, the Indian-led team started their climb in mid-September, lugging antennae, radio transceivers, and a nuclear power supply. By mid-October the team was only a few hundred meters from the summit when a blizzard slammed into Nanda Devi; the commanding officer, feeling conditions were too dangerous, ordered the team to secure the equipment, including the plutonium-powered energy source, and return to camp; because of the horrible weather they eventually needed to abandon the mission. Return missions over the next few years were unable to locate any of the equipment via visual search nor by radiation survey.

According to an April 17, 1978 discussion within the Indian Parliament the device contained two to three pounds (roughly speaking, 15,000-20,000 Ci) of Pu-238 in the form of a metallic alloy that was contained within multiple leak-tight metal capsules; the innermost capsules were made of tantalum metal about 2 cm thick, chosen for its strength and corrosion resistance, and the outer capsules were made of a nickel alloy chosen for its strength and temperature resistance. The capsules were embedded in a graphite heat sink, along with the thermocouples used to turn heat into electrical energy; all of this was surrounded by an aluminum casing. Overall, the device was a cylinder about 14 inches in diameter and 13 inches in height and weighed just under 40 pounds; the SNAP 19C produced about 30 watts of electrical power – enough to light a few night lights.

In 1967 another mission placed a short-lived device on the nearby peak Nanda Kot that collected some useful information about China’s nuclear capabilities before it lost contact. Making yet another ascent to check on this listening station the team found its plutonium power supply had melted its way into the snow and ice, forming a cave melted out to about eight feet in all directions. And this is likely what happened to the device on Nanda Devi – it most likely melted its way down to rock and came to rest inside a small cavern of its own.

This view is not universal, however. Part of the problem is that the glaciers of Nanda Devi melt every summer and their meltwater runs west, into the Ganges River; a river that’s sacred to India’s hundreds of millions of Hindus in addition to providing water that helps support more than a half-billion people through irrigation, watering livestock, bathing, and drinking. Given plutonium’s chemical toxicity, it’s reasonable to wonder if some of the device’s plutonium might have found its way out of the RTG and into the waters of India’s sacred river. And this is where the details of the device’s construction are important.

The outermost capsules, for example, are made of a nickel alloy. Interestingly, some of the alloys used in nuclear reactors include nickel for exactly the same reasons they were used in the lost RTG – it’s strong, tough, and doesn’t corrode very easily in a much harsher environment than a mountain glacier or a river. Tantalum is also known for its corrosion resistance and its strength; the plutonium was sequestered from the environment by multiple layers of metals known for their ability to withstand harsh environments which bodes well for its ability to contain the plutonium. And even if all of those layers do fail, plutonium itself is fairly insoluble. All of this means that the plutonium is going to remain safely locked away for centuries to millennia.

The New York Times article correctly noted that, what with the huge volumes of water flowing from the glacier and down the Ganges, any plutonium that might, somehow, leach out of the RTG will be diluted to undetectably low levels. But the article is a little misleading by failing to explicitly state that Pu-238 is not the nuclide that can be made to explode – it mentions that, unlike in nuclear weapons, there’s no “trigger”…but it doesn’t mention that nuclear weapons don’t use Pu-238 so, even if there were a trigger, it still couldn’t explode.

There’s a lot more to this story, but we’ve pretty much exhausted the radiological parts, so this seems a good place to stop. If you’re curious about the other aspects (and there are some fascinating details), there’s a good Wikipedia article about the SNAP devices, another good one about the Nanda Devi expedition, and even a link to a letter to President Carter from the House of Representatives, all turned up using the search terms “nuclear generator lost in Himalayan spy mission 1965.”