On my very last day at Naval Nuclear Power School, in addition to doing a lot of paperwork and receiving our orders and still more paperwork to bring to our next duty stations, we were sent to the only room at Nuke School that had room for our entire class. There, we heard about the loss of the USS Thresher (SSN 593) and what happened to cause it to sink. And then we were shown a movie about a nuclear reactor accident in the desert of southern Idaho. The discussion of the Thresher got my attention – I had already volunteered for submarine duty (and, as it turned out, I ended up on one of Thresher’s sister ships – but that’s a story for another time) – but there was something about the reactor accident that riveted my attention, including the fact that, since all three operators died, nobody was quite able to figure out exactly why the accident happened. Even today, in spite of the engineering investigations, scientific publications, and popular accounts, we’re still not quite sure about what, exactly, caused the accident – the reason is that it was due to the actions of a single person, and that person is dead and can’t tell us why he took the actions he took. It was this human factor that caught my attention.

But I’m getting ahead of myself – let me go back to the start.

In the 1950s it was clear that the Navy’s nuclear power program was going to be a success and other branches of the military became interested in what nuclear energy might do for them. The Air Force began experimenting with, among other things, nuclear-powered aircraft and the Army looked into developing small land-based nuclear power plants that could be easily transported by truck or airplane and used to power remote bases – the SL-1. As an aside, there were some non-military programs aimed at developing spaceships powered by nuclear reactors or driven by nuclear explosions – which sounds like a good topic for a future blog posting!

The SL-1 reactor was the Army’s first design of a “stationary, low-power” nuclear reactor. The prototype of this reactor was built at a government facility in the desert of southern Idaho, not far from the Navy’s prototype submarine and carrier reactors, the Air Force’s nuclear airplane project, and a few other military or military-adjacent nuclear projects.

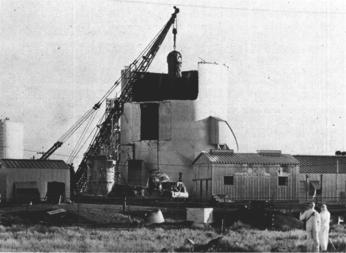

US Atomic Energy Commission image of SL-1 reactor core being removed from National Reactor Testing Station facility in Idaho

Along with its other specifications, the Army wanted a reactor that could be operated by a small number of people – the design that was constructed in Idaho was fueled with uranium enriched to the same level as the uranium used in nuclear weapons, arranged in an array that included nine control rods. In a nuclear reactor, neutrons caused by one fission fly out of the fuel rod and into the water in which the core is immersed; while in the water the neutrons lose energy and slow down, becoming more effective at causing fission. Neutron-absorbing control rods can be inserted into the reactor core to soak up these neutrons, shutting down the reactor; pulling the rods from the core will allow the reactor to start up. Normally a reactor’s control rods are moved by a motor, hydraulics, or some other sort of mechanism – in the case of the SL-1 the reactor sat in a pool on the main floor of the containment structure, beneath some radiation shielding. The operators could actually walk out on top of the reactor when the reactor was shut down and radiation levels were low.

So…with that as a prelude, here’s what we know about the events of January 3, 1961.

Following a holiday shut-down and maintenance period the three operators, Army Specialists John A. Byrnes (age 22) and Richard Leroy McKinley (age 27), and Navy Seabee Construction Electrician First Class (CE1) Richard C. Legg (age 26) were starting the reactor. At 9:01 PM Byrnes abruptly pulled one of the control rods, causing a sudden and dramatic increase in power. In the next few seconds, much of the fuel either melted or was vaporized, the sudden input of thermal energy caused some of the water in the core to flash to steam and the steam explosion shot jets of water out of the reactor core and caused the entire reactor to jump upwards by about nine or ten feet and spraying the inside of the containment structure with radioactive water. The pressure also shot the #7 shield plug out of the top of the reactor vessel; standing above it was Richard Legg, who was impaled by the plug and pinned to the ceiling of the containment structure.

The other two operators were apparently standing nearby at the time of the accident and were also killed by the accident – it’s possible that they were killed by the shock when the reactor jumped upwards so violently and the impact of the operators with the reactor. Byrne and Legg appear to have died instantly, McKinley seems to have survived for an hour or two before succumbing to his injuries. Although all three men died of physical trauma from the explosion, they received a dose of radiation that would have been fatal even in the absence of their injuries.

The aftermath of the accident unfolded over the next several years and included an extensive investigation as well as decontamination and demolition of the reactor plant along with radiation surveys and decontamination of areas surrounding the reactor site. But – and this is the part that fascinated me – there is no definitive way to know why Byrnes was standing over the reactor, manually pulling the control rod.

The story I heard was anecdotal; one of my classmates said he’d heard that Byrnes had learned that his wife was having an affair with one of the other two operators – that he had deliberately caused the explosion to either commit suicide, to try to kill his wife’s lover, or both. That was the conclusion of one popular account of the accident as well. The problem is that there’s no way to prove – or to disprove – this hypothesis. Not only that, but there are plausible explanations other than murder and/or suicide.

As one example, the control rods sometimes stuck in their channels; it’s possible that Byrnes was trying to free a stuck rod and, when it finally came free, he was pulling so strongly that the rod traveled far past the point at which the reactor became critical, causing it into a dangerous condition known as “prompt criticality” in which power increases uncontrollably.

The rod might have been pulled inadvertently, perhaps by an operator expecting some resistance and finding none.

Or the operators, noticing the rod having a tendency to stick when moved, might have been trying to move it up and down by hand until it was able to move smoothly, accidentally jerking it upwards.

Unfortunately, the operators failed to make any notes in their operating logs that they were having problems with any of the control rods or that they would be working on them.

Thus, my fascination with SL-1. First, at the very start of my stint in the Navy’s nuclear power program, it was sobering to hear of an accident that had cost the lives of three military operators; just as hearing the technical details was fascinating. Hearing how the accident was re-created and what the investigators were able to learn was fascinating, sparking that part of my mind that had so enjoyed reading Sherlock Holmes stories when I was younger. And adding in the fact that we might never know exactly why it happened – plus a little bit of spice with the suggestion that it might have been the result of a love triangle…that made it irresistible.